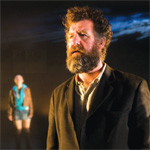

Immediately arresting in this production of Deirdre Kinahan‘s new play, BogBoy, at the Irish Arts Center, is Ciaran Bagnall‘s simple stage set of several scrim panels reflecting projected landscape imagery. The mood is heavy and still – darkening flat vistas of bogland stretching off to meet a cloud-crowded sky broken only in places to admit thin fissures of light. The colors shift slowly between sombre browns and blues, with occasional russet veins of sunset. Amorphous, echoing sounds groan forth creating a mournful, timeless feeling. This is a bruised place. Into this scene walks Brigit, a woman as bruised as the landscape, but prickly, defensive, and verbally alert. She is a Dublin rehab patient, a former heroin addict and prostitute, transported to the rural remoteness of Navan, Co. Meath, and initially utterly at sea in this natural wilderness. Warily she begins an acquaintanceship with her neighbor Hughie Doyle, a solitary, slow-thinking bachelor who seems to her as foreign as the landscape. Gradually we watch as their sad stories unfurl.

Originally written for radio, BogBoy retains some of its original source characteristics. It is short, tightly compact, structurally sophisticated, and brisk in the manner of its verbal exchanges. Jo Mangan‘s direction keeps things moving rapidly and this works well with the tone and tempo of Kinahan’s language. Admirably matter-of-fact and colloquial, Kinahan does permit herself the odd shift to a more lyrical register, introducing some vivid descriptive color to the characters’ humdrum exchanges. Brigit, in a letter, waxes unusually eloquent on her discovery of the bogland’s hidden natural charms. But the dominant tone, for all the aura of tragedy here, is low-key. We observe mundane instances of neighborly exchange between Brigit and Hughie that serve as views to an evolving friendship, opening the door just a crack wide enough perhaps to admit hope. Hughie teaches Brigit to ride a bicycle in a light-hearted scene that has everything to do with empowerment, but which spends no time mulling over the fact. Beginning with just this slender degree of interaction, two psychologically convincing characters, relaxed and in extremis, the story stretches effortlessly to encompass themes of political, social, and historical relevance for contemporary Ireland, north and south, urban and rural. Everything resides most naturally within the unfolding drama. There isn’t a whiff of a sermon here, just the sad appraisal of human damage in the aftermath.

Mangan’s choice to have the characters direct nearly all of their dialogue outward, face forward toward the audience, is compelling and intriguing. We get to witness fully the emotional nuance in their faces, as well as some considerable craft in actorly responsiveness. There is also the suggestion that, as much as they want to connect, these characters can never truly face each other. Sorcha Fox is winningly forceful, bossy and vibrant as the wounded Brigit. She embodies an instinctual energy that livens the atmosphere, her large eyes wide and boldly defensive. Steve Blount, resolutely inarticulate as Hughie, is bemused and enthused by her brio, and there is a fine comic contact quickly established between the two. Rounding out the cast are Noelle Brown as Annie, Brigit’s skeptical if well-meaning social worker, and Emmet Kirwan as Brigit’s scathed and unforgiving husband, Darren, both assured turns in brief parts. Philip Stewart supplies the effective sound effects.

This is an impressively compacted story which errs, if it does so, on the side of brevity, driving us rapidly to an abrupt, almost brutal conclusion. I couldn’t help feeling that there’s at least another scene or two tucked into the narrative. A tale of would-be redemption, it never quite gets there for these two lost characters. Neither have the strength to overcome the forces surrounding them. In a letter she is writing to a murdered boy’s sister decades after the event, Brigit describes having seen the sister in the landscape once, surrounded by “bogmen guards” who seem themselves to have emerged from the muck of the bog. But to Brigit, the woman appears distinctive, separate, in a tight white suit with sunglasses – an anomaly in the landscape. For Brigit she is the definition of freedom, success, escape. But, just like all the characters here, this idealized, seemingly emancipated figure will never truly be rid of the bog. A part of her is buried here. Brigit’s letter, an intention she feels is finally something wholly good, will recall the woman once again, oblige her to step into the muck again, albeit to retrieve something ultimately lost. Kinahan’s play has many hidden leaves like this. It could go on unfolding.

~~~

BOGBOY Written by DEIRDRE KINAHAN Directed by JO MANGAN Design by CIARAN BAGNALL . September 7 – 25 Wednesday – Friday | 8 pm Saturday | 2 pm & 8 pm Sunday | 3 pm . Irish Arts Center Donaghy Theatre 553 W. 51st Street New York, NY 10019 between 10th and 11th Avenues . Click Here for tickets Running time- 1 hour / NO LATE SEATING

{ 0 comments… add one now }