She was an original. Tempestuous. Tormented. Talented. A trailblazer. Triumphant even in defeat.

Patsy Cline was one of a kind. Today, on the occasion of what would be her 80th birthday, September 8, and the exhibition Patsy Cline: Crazy for Loving You in her honor, mounted at Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame, is an opportunity to look back at the life of this legendary and innovative recording artist.

Sadly, just when the best of her life began, it ended: March 5, 1963, when on the journey home from Kansas City, after performing at a benefit, she, her manager Randy Hughes, and Grand Ole Opry stars Hawkshaw Hawkins and Cowboy Copas were killed outside Camden, Tennessee, in the crash of Hughes’ four-seater airplane.

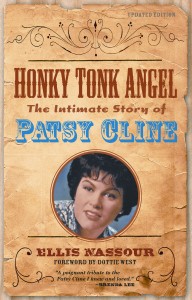

For 18 years after her death, following the impact of such a great loss to country music and the entertainment world, virtually nothing was written of this unique personality. Then came Vicksburg, Mississippi, native Ellis Nassour’s first biography on Patsy Cline. He’s devoted a good deal of his career keeping the legend alive and growing.

Though she died shortly after turning 30, Patsy left behind a rich personal and musical legacy. She has developed cult followings around the world, especially among young fans who are mesmerized by the hurt in her voice that, many agree, is yet to be equaled.

Patsy is more famous in death than she was during her lifetime. It seems the world cannot get enough. Nassour had a brand new Collector’s Edition hardcover Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline published in 1993. Others have attempted to tell her story. From the acclaim for Nassour’s biography, published in an expanded edition in 2008, it’s considered the best and the most definitive.

Patsy is more famous in death than she was during her lifetime. It seems the world cannot get enough. Nassour had a brand new Collector’s Edition hardcover Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline published in 1993. Others have attempted to tell her story. From the acclaim for Nassour’s biography, published in an expanded edition in 2008, it’s considered the best and the most definitive.

“I was blessed to be the first to write about Patsy,” says Nassour, “and the only one to interview so many intimates, including her two husbands and her mother.”

According to Nassour, Patsy was “a good ole country gal, very used to getting her way any way she could get it. She was equipped with talent that even she didn’t know she had and raw ambition to become a star on the Grand Ole Opry.”

From her early Virginia days, Patsy struggled to make a name for herself. “As sweet as her music could be,” observes Nassour, “her personal life was as passionate as it was reckless. She was a rebel and a homewrecker. She wanted fame so badly she let nothing and no one stand in her way.”

Born Virginia Patterson Hensley near Winchester, she possessed from the earliest age a self-assurance that made her believe not only that she could be the best female singer in country music but also that she was. Nothing could daunt her. A saying sprang up about Patsy: “She’s not conceited, she’s convinced.”

Patsy never had lessons; but from age eight, when she began singing on street corners and in her church choir, she had the most incredible voice. She had aspirations of being the youngest star ever on the Opry. She sang anywhere she could: as a child on street corners; then, in church; and later, “tired of waiting so long to be discovered,” bursting into a radio station at the age of 14 to demand they put her on.

“They did,” explains Nassour, “and she didn’t make a fool of herself. Locals laughed at her dreams, which didn’t faze Patsy. Her goal almost came true when, at age 14, she auditioned for the Opry. It was a lost opportunity for many reasons, but Patsy returned home more determined than ever.”

So determined, in fact, that she made costly mistakes, such as allowing the older bandleader she worked for (and with whom she was having an affair) to sign her to a self-defeating record deal in the late 1950s. In the male-dominated country arena of that era, women were part of a show or sang with their husbands. “That wasn’t for Patsy,” notes Nassour. “She wanted to be accepted as a solo female artist, which didn’t go down too well with the male stars, but she eventually won out. ‘Overnight fame’ helped.”

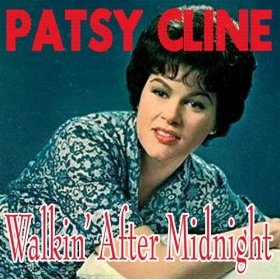

Though she’d starred on Jimmy Dean’s regionally-syndicated variety show out of Washington, Patsy’s breakthrough came in 1957 on CBS’ Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts, which showcased budding professionals and amateurs. She won with a decidedly non-country song, “Walkin’ After Midnight,” which had been passed over again and again, that her label made her record.

“She hated it,” says Nassour, “and not just because it was crammed down her throat. She told friends it made her feel like a streetwalker. Godfrey liked the tune, however, and refused to budge when she wanted to sing country and yodel.”

Godfrey felt he’d discovered the real thing and hired Patsy. They clashed constantly. He fired her two weeks later!

“Walkin’ After Midnight” was huge and, in a first for a country female, crossed over to the pop charts. Patsy got to tour solo. You can’t argue with success. She proved a country female could draw audiences and, as Nassour observes, “not be window dressing for some male artist. It also led to her first album. The male stars and many in the industry considered her a fluke. The gals not only looked down on Patsy, who could be, to say the least, one of the guys; but also found her outfits distasteful.”

“Patsy dropped the de rigueur ‘cowgirl’ look,” continues Nassour, “for what she considered New York glamour. That actually meant sexy, which got her into a lot of trouble with the family-oriented Opry. Before long, however, the gals who gossiped behind her back began copying Patsy. None had her success, but Patsy befriended them all.”

Patsy was soon an Opry star. Her song sold well for over a year. Due to the constrictions of her contract, stipulating she could only record what the label dictated, it was followed by four dry years. If Patsy could not lay claim to birthing what became known as the Nashville Sound, she brought it out of diapers. And, not willingly. She loved pop and rock music, but preferred to record country – the hillbilly kind. Enter big bandleader and pianist and Nashville Decca Records producer Owen Bradley, who introduced her to up-and-coming songwriters Harlan Howard, Hank Cochran, and Willie Nelson.

Nassour notes that Patsy had “the ability to segue from hayseed to heartbreaking ballads. Bradley coerced her to record songs from the 20s to the 40s, which he gave a new spin. He claimed Patsy could sing anything and discouraged her from her desire to yodel.” He surrounded Patsy with Nashville’s best musicians as well as backup singers such as the Jordanaires, who were associated with Elvis’ early work.

Bradley knew he had a star; he had to convince her. He pushed Patsy – sometimes screaming and fighting – where she never thought she could go. He broke Nashville taboos, adding strings and drums and soaring arrangements to her sessions. “To get his way,” explains Nassour, “he’d select tunes he wanted to record; she selected those she wanted. He’d get one, she’d get one! This kept her popular with country fans while expanding her pop audience. Then, artists were either country, rock, or pop. Today, where lines are easily crossed or merged, it’s hard to image the impact Patsy and Bradley had.”

Patsy hated “I Fall to Pieces,” which took six months to begin its ride up the country and pop charts. She hated “Crazy.” “But,” laughs Nassour, “when they became hits, earning big money, Patsy, always struggling financially, grudgingly admitted she warmed to them. She wanted to sing up-tempo, but Bradley convinced her ballads were her bread and butter.”

According to Nassour, vocally, Patsy Cline had a majesty and poignancy many say have never been equaled. “She could produce extended Western yodels, but also sweeping high notes. She had amazing dexterity, switching from a country hoe-down to vintage Irving Berlin or Cole Porter and torch ballads written for her.

Patsy was on the charts, selling albums, touring, headlining with Johnny Cash, doing TV, and making money. She was generous to the gals coming up the ranks, helping Loretta Lynn and Dottie West, as they began their careers, and being a big sister to her beloved Brenda Lee, who, reveals Nassour, credits Patsy with teaching her words her mother didn’t approve of.

Patsy Cline’s impact on the industry was such that “Faded Love,” recorded days before the fatal crash and which had been a huge hit for a number of country male stars, became a posthumous hit. Today, it’s only remembered for Patsy’s poignant rendition.

In 1973, in tribute to her incredible popularity and artistry, she was the first solo female named to the Country Music Hall of Fame. She left behind a great musical legacy, honored in 1995 with a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement.

In 1973, in tribute to her incredible popularity and artistry, she was the first solo female named to the Country Music Hall of Fame. She left behind a great musical legacy, honored in 1995 with a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Patsy Cline influenced legions of performers. In 1997, People Magazine named her to its list of The Most Intriguing People of the Century. Patsy took her crossover appeal to New York’s Carnegie Hall, Las Vegas, Los Angeles’ Hollywood Bowl, and even to the TV teen dance show Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. She won countless music awards with her landmark hits “I Fall to Pieces,” “Crazy,” and “She’s Got You.”

“She brought happiness to millions,” Nassour points out, “but had a difficult time finding it in her personal life. Though Patsy and second husband Charlie Dick were deeply in love, as her fame increased they made recriminations against each other. He couldn’t cope with her success and long absences. A heavy drinker, Charlie’d berate her in public, hit her, and Patsy’d famously fight back.

He’d accuse her of infidelity, when he was the guilty one, and being an unfit wife and mother. “Patsy was in a near-fatal automobile crash in the summer of 1961,” continues Nassour, “and had a nervous breakdown as she attempted to get back to work too soon. She was plagued with bouts of depression and felt her terrible scars drove Charlie further away.”

Just as Patsy re-established her place on the charts with “Crazy” and “She’s Got You,” she began contemplating a break from Charlie. Then fate intervened.

Returning from Missouri, fighting thunderstorms all the way, Randy Hughes landed in Dyersburg, Tennessee to refuel for the last leg. Warned against continuing, Hughes, who wasn’t instrument trained, boasted he’d flown the area many times. Within 20 minutes of take-off, the skies darkened. He lost visibility. From the way the plane crashed, the FAA assumed he was flying upside down. Only three albums were released in Patsy’s lifetime, but there were great songs from a session only a month before her death. Patsy Cline’s Greatest Hits was on the Billboard magazine album charts for over 900 weeks. “Crazy” is the Number One worldwide jukebox champ.

Patsy’s gravesite outside Winchester, Virginia, is marked with a simple bronze plaque that reads: Death cannot kill what never dies, love.

“Patsy Cline is remembered today,” observes Ellis Nassour, “because of her indelible gift of music. She was a star when she left us, and a star she remains.”

For more information on Patsy Cline, visit www.PatsyClineHTA.com

{ 0 comments… add one now }