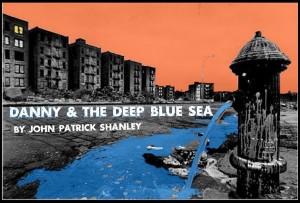

Written in 1983, an early effort from playwright John Patrick Shanley (Moonstruck; Doubt: A Parable), Danny and the Deep Blue Sea has enjoyed a healthy theatrical life to date, being something of a favorite showcase for two actors displaying their mettle in a torrid tale of attraction, repulsion, knock-down and drag-out. At once alive to the profane speech and stunted hopes of its two messed-up blue-collar, Bronx dwelling principals, it is also elaborately artificial in its romantic trajectory, positing the notion that these two social zeroes could come together in the course of one night and offer each other something like redemption – in the form of a marriage proposal. You don’t have to be hyper critical to find it psychologically unconvincing. But you might want to re-examine your own smug sense of what is and is not possible as Shanleys’ characters, Roberta and Danny, play out this tormented encounter with the demons that preside over what can and cannot happen for them in their own desperately bleak lives.

At play’s opening Roberta (Allison Plamondon), sullen yet provocative, sits alone in a dive bar, drinking. Enter Danny (Joe Perrino) holding a pitcher of beer, bloodied and still steaming from a recent violent street encounter. He takes the table alongside Roberta. The pheromonal hum he’s giving off would move most people directly toward the exit, but to Roberta it works as an enticement. She engages him. In short order Danny has convincingly asserted that he is homicidal, and Roberta that she is suicidal. A perfect match in some ways, but the verbal sparring that ensues, escalating quickly to physical assault, offers not a shred of comedy, or even tragedy, as respite. As blinded with self-loathing and rage as his characters are, Shanley finds language for them to convey the greater evils of their lives – a generational despair passed on by parents who long ago lost any self respect, along with their way. A kinship evolves and as rashly and ill-advisedly as anything else they have undertaken, these two move from bar room to bedroom. Post-coital the tension eases to a degree, but in another way the real fighting for this couple is just beginning.

Each has a sense of a better life – as clichéd and romantic as can be – and following the savagery of what went before, a certain lame tenderness is aired between them. The mythos of marriage takes hold and there’s a measure of ghastliness about the tired projections the duo concoct for themselves. Shanley puts romance on the operating table and invites the audience into the surgical theatre. Stars in a night sky induce a headache in Danny, until finally he can see some that form themselves into - a big lump of tuna. Roberta watches the glow of a red garage light outside her window and fantasizes it’s the moon. Even these two headcases can tell themselves stories, but can they find a different ending for the one they’ve been telling themselves all their lives?

If you don’t believe Shanley’s story, it won’t be on account of director Alice Spivak. Spivak, a veteran acting teacher and coach, throws all her energy into drawing performances from her actors, both incidentally past students of hers. She certainly appears to know how to get what she needs from them. Character comprehension and projection is deep core. Perrino’s hopped up, thin-skinned aggression relents to just as tongue-tied a vulnerability once, unwisely perhaps, it senses safety around Roberta. Wide-eyed, muscular, prone to fits of breathlessness, every tic and posture broadcasts a hair-trigger, dangerous sore-head inviting some kind of hormonal intervention. Sporting a pair of amateurishly blood-laced knuckles, Perrino easily disposes of a clumsy theatrical effect that more readily suggests a run in with a raspberry syrup dispenser than the result of a bruising street brawl. Plamondon’s Roberta is shrewder, crueler perhaps in her calculating approach. Arrogantly abandoned to her own hopelessness, Plamondon gives Roberta a brazen stare and a mouth that most naturally relaxes into a lop-sided smile of contempt. For all her armored defiance she is see-through when desperate. She knows that she needs to be forgiven, but is not clear if she wants to be punished more than she wants forgiveness. Catholicism gets a shout-out here, and we get a riff of comedy as the pair consider the possibility of a protestant wedding ceremony. There’s a definite chemistry between these two, which drags you along for the ride however much you might protest the credibility of the scenario. Their convincing embodiment of the characters actually works at throwing the artifice of Shanley’s piece into relief. Which itself is a nice conceit, one the playwright might approve.

Minor quibbles would mention the poor sighting in sections of the auditorium’s seating during some of the action. The stage at the Nuyorican Poet’s Cafe is quite low and one scene has the characters prone on a bed for exchanges. There’s enough real blood in the language and the performances to overlook the aforementioned poorly applied theatrical kind. Indeed, perhaps there’s something to be said in favor of the belaboring of this gory illusion. The best theatre teases us with the knowledge of its artificiality, even while it pulls us into a state of credulous surrender. All evidence suggests this production, from OnTheRoad Repertory Company, is vividly wise to this understanding, and sharp about how to convey it.

{ 0 comments… add one now }